l e t t e r f r o m a f g h a n i s t a n p e t e r c h u r c h

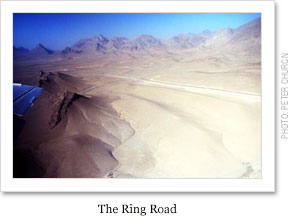

The road out of Farah is hardly a road. It’s a bumpy scrabble track over a vast desert basin where the mountains on the horizon never grow or shrink. You cross the desert to get to the Ring Road. That takes three hours—past isolated clutches of low, domed mud huts off on the expansive horizon; along the dry-as-a-bone River Farah; past a few miraculous poppy fields. They’re miraculous because water in Farah is rare in the best of times, and even more so when there’s been a seven year drought. What vegetation exists in this desert looks dead. And yet somehow farmers coax poppy from it.

Occupations of Farah stretch back at least 2,500 years. The massive, weathered earthen walls of an ancient citadel called Shar-e Farahdun remain atop a low rise a short distance from Farah’s bazaar, or main street, where men in turbans lie languidly in the shade of shops that all seem stocked with the same goods. The citadel is said to have been built by a Zoroastrian warrior in the time of Darius the Great (reigned 522-42 B.C.E.), though in the ‘80s, the mujahadin used it as an arms depot. Its expansive interior remains littered with unexploded ordinance, which doesn’t stop locals from gathering there for dog-fights and picnics.

Shir, or “Lion,” is behind the wheel. The desert meets the sky in a circle all around us. His face is weather-beaten; his eyes are icy blue—they make you think of water. His smile is warm and his voice sounds like the low register of a cello. He is only about thirty-five but could pass for sixty. On his left hand is a tattoo—madar, mother. He is proud of his four children. He is uneducated but incredibly curious. He thinks for long stretches, cobbling together questions with his meager English. They usually begin, “In your country . . . .?” I meet him with my meager Dari, and we laugh. The questions come steadily but well-spaced: In your country, roads like this? In your country, weather like Farah? In your country, there are mountains?

How do I explain America? Yes, some roads are like this, I say. Should I try to describe the New Jersey Turnpike? Yes, some weather in America is like in Farah. Should I try to explain the Pacific Northwest? Summer thunderstorms over the Great Plains? A New England autumn? Yes, there are mountains in America, but not big like Afghanistan mountains, I say. Shir smiles.

We drive past herds of Dromedary camels and goats grazing on what small offerings the land provides, some lonely shepherd in their midst, not a spot of shade in sight. What does he eat? Where is he from? Where is his family? Where does he sleep at night? Past an abandoned carwan-sarai—caravan house—a large, fort-like enclosure left from the days (not so many years ago) of camel caravans between Herat and Kandahar. The carwan-sarai are spaced every thirty miles or so, a day’s walk. In its day, Farah would have been a minor way-station on the Silk Road network between Persia and India, between which traveled textiles, spices, and treasures. Today Farah a conduit for another kind of traffic: opium to Iran, arms to Kandahar.

In your country, you have camels? In your country, there are Muslims? In your country, how many mosques? In your country, how much for a wife? In your country, people are rich or poor?

No, we don’t have camels in America. What’s the word for “zoo”? Yes, in my country there are many Muslims and many mosques. In my country Musselman (Muslims) and Massi (Christians) live together. In my country, wedding is not like in Afghanistan, I say. In America some people are rich and some are poor. How do I explain relative standards of living? How do I explain taxes and welfare to someone who has lived in a dusty corner of a country without anything worth calling a government since he was a boy?

At the Ring Road we turn north to Herat. The condition of the Ring Road varies between concrete in severe disrepair, asphalt newly laid by a Turkish construction company, and just plain old bombed-out: craters in the road and the leftovers of bridges. We have to detour around sections under construction or destroyed.

All along this stretch of the Ring Road are piles of rocks, some painted white and some, red. Afghanistan is one of the most heavily mined countries on Earth. There are de-mining efforts all across the country, but hundreds of people die every year as a result of mines nevertheless; though, every year a handful of people in France are killed by unexploded WWII ordinance as well. The white rocks indicate areas that have been de-mined and the red rocks indicate areas that have not been.

The detours lead us off the road, often through patches of white rocks. But no de-mining campaign is 100 per cent effective, and it only takes one overlooked mine to ruin your day. Shir reads the concern on my face, smiles, and says what Afghans always say: No problem. Just stay in the tracks, I think to myself.

The completion of the Ring Road is, or will be, probably one of the most important means of unifying this country that has always been divided by geographic obstacles, to say nothing of the political-ethnic divisions that those geographical obstacles aid. The Ring Road may be no wider than a two-lane country highway, but it’s a road of lofty intent. It’s meant, in part at least, to help build an Afghan national identity, just as the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad did for America in 1869, bringing physically together a nation of distances and obstacles that had been embroiled in a bitter Civil War only four years earlier. Here, though, better roads also mean easier drugs and arms trafficking. I doubt there will be a golden spike.

To illustrate the importance of completing the Ring Road: Herat is about 180 miles from Farah, but it takes roughly seven hours to get there.

Founded by Alexander the Great in the 4th century B.C.E., Herat has been an active center of culture and commerce ever since. Today it is perhaps Afghanistan’s nicest city. It has only a quarter of the population of Kabul, less pollution, more trees, more public parks, and more historic architecture in tact. During the Soviet jihad this was Ismael Khan’s stronghold, and he defended it fiercely.

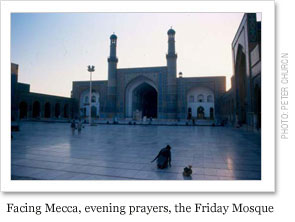

The old section of Herat is dominated by the famous Mosjid-Jamé, or Friday Mosque, also commonly called the Blue Mosque of Herat, built in 1200 on the sight of a 10th century mosque. Genghis Khan laid waste to Herat in the 1220s and legend has it that the only people in Herat to survive his slaughter were the six hiding in the Blue Mosque. Tamerlane made Herat the capital of the Timurid Empire in 1383, sparking the Timurid Renaissance, when Herat would become a major center for learning and the arts. The Timurid Renaissance was driven largely by Tamerlane’s daughter-in-law, Queen Gaward Shah, who sponsored a great deal of building and learning.

In the north of Herat stand four tall minarets at the corners of what was a madrassa inspired by Queen Gaward Shah, built shortly after she was poisoned at the age of eighty in 1457. In a country where the average lifespan today is forty-three years, eighty remains an impressive age to achieve. The minarets are an impressive three hundred-some feet tall but in sad repair, and, helping to hasten their collapse, are constantly shaken by the traffic that passes at their base.

Between the Blue Mosque and the minarets is the Citadel of Herat. Built in 1305, it became the center of the Timurid Empire for most of the 15th century. You go down the street and there it is, seven hundred years of history sitting unceremoniously behind a narrow lane of welding shops, smithies, carpenters, and other merchants. Genghis Khan fought here before it was built. After building it, Tamerlane fought in its shadow. A restoration project begun in the 1960s and suspended by 25 years of war is beginning to be taken up again. Small patches of blue tile still cling to the Citadel’s upper heights. A young man who spoke some English approached me, and I asked him about the citadel. He told me that it is very old, older than the automobile. I asked him if he was sure about that. He opened his eyes and said earnestly, Yes, for sure. I told him that the automobile is only about 120 years old. He was surprised to find out.

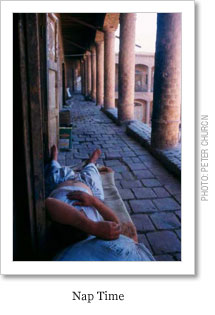

In the afternoon I wandered through the narrow back alleys around the Blue Mosque and through the maze of covered market-squares hidden down narrow alleys behind the shops lining the streets. I was looked on with curiosity everywhere, and invited to drink tea at almost every other stall. I drank tea with the proprietor of one of the dozens of burqa shops. That’s all he carried in his stall. His son was with him and he showed me the stitching and designs, saying proudly that he did the sewing himself and that he has owned the shop for fifteen years. The size and the embroidered designs around the face-screen differed, but they were all blue. At another burqa shop around the corner from his, I watched a man and his burqa-covered wife talking back and forth, presumably discussing the merits of the handiwork of several burqas, all in the same shade of blue.

In the carpet bazaar I made a friend, Amir, who closed his shop so that he could guide me through the streets. He took me to an old, enclosed market house that, he said, was maybe 500 years old. The brickwork was intricate, and the columns had beautiful detailing. But it was in a sad state of repair. Amir told me that the Taliban used it as a prison; his father had been imprisoned there because his hair was unacceptably long. Now, old men sit on the thresholds of the small rooms that serve as sewing shop and bedroom in one. Amir told me that the Taliban were stupid. They would hit you if you didn’t pray right, he said. But Allah wants us to be free to pray to him. From the roof of this old market you can see across the rooftops of the old section of the city. In the distance you can see the citadel and the tips of the four minarets and the Blue Mosque. You could probably walk across the rooftops for half a mile.

In the evening I walked to the Blue Mosque and was told by a Kalishnakov-slinging guard that I could not enter until after prayer time because I was not Muslim. I asked him how he knew that I wasn’t Muslim. Are you Musselman? he asked curiously. In Arabic I recited for him the Muslim invocation: There is no God but Allah and Mohammed is his Prophet. He kissed me on the cheek, stood to the side, and with a smile said, Come with me.

He led me through a covered passage and into the massive open center square where I found myself, having arrived late, facing a few hundred men lined up for prayer on a carpet running the width of the square. I looked at them, they at me. It was a bit like walking onstage before an audience. Never before had the absence of a turban on my head been so profoundly obvious. Act like you belong, I told myself. I took off my shoes, put down my backpack, and joined the men, mimicking their prayerful gestures. The men around me looked at me curiously. Word must have made its way down the line, because from the corner of my eye I could see men farther off sticking their heads up for a better view of me when they should have been bowing.

The sun was setting. The wall of ornate blue tiles on the eastern side of the square glowed in its light, as though the wall were a window looking into the infinite blue of God. The marble blocks on the floor of the square held the heat of the day and the warmth was soothing on the bare feet. After prayer, as I was milling about admiring the Mosque, I was approached by a high school student studying for exams. He was eager to use his English and told me that he was glad to meet me. An old man with only a handful of teeth approached and, with the help of the student, said that I was his guest in Afghanistan and that he was glad that I was here. I thanked him, and told him that I, too, was glad to be here.

They both wandered off. Another man approached. He asked if I spoke English and said that this Mosque was only for Muslims, adding that he did not think I was Muslim. How do you know that, I asked. He looked me up and down and said, You do not look Muslim, then asked, What is your name? I told him, and he repeated, I do not think you are Muslim. You must go away. While I had a beard, this man had none: I don’t think that you are Muslim, I said. Where is your beard? My beard is bigger than your beard. About the time it occurred to me that this was neither the time nor place to try to win an argument, the high school student returned and scolded the man. Fortunately, the man didn’t make a scene. I asked the boy if I should go. No problem, he said.

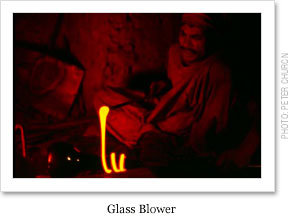

In the setting sun I walked out the northern gate of the Blue Mosque and, crossing the street, found a famous resident of Herat, Haji Sultan Amidi. Haji is an honorific reserved for those who have made the haj to Mecca. Haji Sultan is the living patriarch of a family that has blown the famous blue glass of Herat since Genghis Khan’s time. His story is myth mixed with history, which helps him sell his family’s blue glass.

Today, the glassblowing is done by a small, hunched-back man named Tokhlan Saqui. He sits in a cave-like shop with earthen walls and a low ceiling across the street from the Blue Mosque and a few doors down from Haji Sultan’s shop front. Tokhlan Saqui hunches over his kiln and with nothing more than fire and water and a blowing tube, crafts his glass. As the sun had dropped below the horizon, the only light in small shop came from the fire. His skin glowed a deep orange, as though embers were below its surface. With his glass-blowing tube he extracts molten glass from the kiln the color of a harvest moon and dripping like burning honey. He blows into the tube and the glass expands, he shapes it with a prong, he returns it to the fire and repeats. When he’s satisfied he then drops it into a bucket of water that erupts in steam. When the glass has cooled, you can’t believe it was fiery hot, because now it’s the color of the cool sky.

On the road back to Farah, a swath of concrete and asphalt bisecting an endless landscape of dun crags and emptiness. What kind of animal is that walking beside the road ahead? It’s not an animal; it’s a man, a man so crippled that he can only hobble along on all fours, moving as a lame dog might. The mid-day sun fiercely pounds the earth. It bleaches the sky. The cripple pulls himself over the dirt and rocks. There’s no town or village, or anything bigger than a truck stop, between Herat and Farah. From where did he start? Where could he possibly be so desperate to arrive? And what’s that on the other side of the road? A herd of camels. And look at the calf suckling from its mother!

The truck I’m riding in has a security escort made up of a Russian jeep crammed with young, armed Afghan soldiers. On one of the off-road detours they drive too fast and flip their jeep, smashing the windshield and crushing the roof. None of them are wearing seatbelts. Two of the soldiers are flung from the jeep. One has some bleeding from his head, but is conscious, the other has a dislocated shoulder and is dazed, but is otherwise fine. Fortunately that’s the extent of the damage. All around us are piles of painted white rocks. The soldiers are obviously in pain, but they are breathing fine and have feeling in their extremities. We dress the head of the one and stabilize the arm of the other. The other soldiers are holding up a syringe and a liquid in a less-than-clearly marked vial and telling me to inject it in the shoulder. For pain, for pain, one of them says over and over. I wag my finger and say that’s a bad idea, taking the syringe and vial—who knows what the hell it is

We’re four hours from Herat. It’s a bit less than that to Farah. Though they couldn’t understand me, I told the soldiers that’s what you get for driving like knuckleheads, consider yourselves lucky it wasn’t worse, and you’ll just have to deal with the pain for a few more hours. We move the wrecked jeep out of the road and consolidate passengers for the remaining hours of bumpy scrabble track to Farah. I give Shir a frustrated look and he says with a smile: No problem.

![]()

Write to us: