m e m o i r s j o h n p a l c e w s k i

![]()

I was conceived the first week of June, 1941, in the back seat of a ‘37 Ford in a driveway in Youngstown, Ohio, around two or three in the morning when all the bars had closed. My mother yielded to my drunken father because he always got so bent out of shape when he didn’t get exactly what he wanted. She knew it would be over real quick, so what the hell. A couple months later she realized what a horrid mistake she’d made that night.

When I was eleven a neighbor lady named Caroline told me that my mother was not dead—as my father had told me—but lived on the other side of town. “She calls all the time asking how you’re doing, Johnny,” Caroline said. “She loves you very much.”

Her name? Elizabeth. Betty for short.

I confronted my father. I said I wanted to see my mother. And I asked him why he’d lied to me about her. “Because she’s a fucking whore,” he replied.

She was a breathtakingly beautiful woman from an Irish family named Joyce. Their house was full of books, and they all gathered around the grand piano and sang sentimental songs, and read poetry aloud. Elizabeth—my mother!—loved opera. Her favorites were Verdi, Puccini, and Bellini. Every Saturday she listened to the Texaco Metropolitan Opera broadcast, a habit I picked up, too. My father, of course, had no use for any of this. He loathed her for her artistic bent, but mostly for throwing him out. And what’s more he hated me. Why? Because every time he looked at me, he saw her.

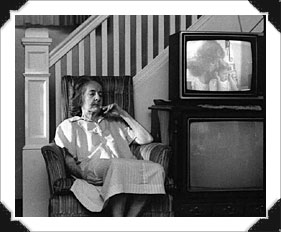

Forty years later, I took a picture of my mother sitting in a chair in the living room, dozing. She was in the final stages of dementia, and no longer recognized anyone. She was infantile, incapable of speaking. Everyone told Bully he ought to put her in a home. They said he couldn’t go on changing her dirty diapers and bed sheets, and bathing, dressing, and feeding her. There’s only so much a man can be expected to do. But Bully said there was no way he’d put her in a nursing home where she’d be mistreated by those people. He’d heard what goes on in those places.

She died about three months later. Bully? He died of heart failure not long afterward. They all said that he didn’t want to live without her.

![]()

When I learned the whole story I didn’t doubt my mother had sufficient reasons for abandoning me.

On March 29, 1940, my sister Roberta Lee was born. Ten months and twenty-four days later Elizabeth went into the bedroom to check on her baby, and found it motionless, pale blue, and cold. She shook Roberta, begged her to wake up. But she was dead. Elizabeth called the ambulance. As they arrived my father came in, staggering and slurring. When they told him the bad news he blinked, unable to comprehend the words. He kept blinking and shaking his head. Finally he collapsed to his knees, his hands over his face, and he moaned.

Josephine, my grandmother, finally showed up. Her sharp eyes darted here and there. She noticed that the bedroom was cool. The window was open about two inches at the bottom. She turned, faced Elizabeth. “This is your fault,” my grandmother intoned. “You’re an unfit mother.”

My father rose from his sobbing. Elizabeth expected him to come immediately to her defense. To point out that Dr. Tamarkin had seen Roberta two days before, and had reassured Elizabeth it was just a bad cold, and that in time it would pass. But my father said nothing. He stood close to tall, grim-faced Josephine. His glaring, angry, and reproachful eyes said he agreed with his mommie. All this was Elizabeth’s fault. “Do you leave a window open all day and night during the winter, especially when a baby has a cold?” Josephine said.

I first heard the story from my father, shortly after he told me I couldn’t see my mother anymore. “Your sister Roberta Lee died because that fucking whore was unfit as a mother,” he slurred. “Unfit. That’s right, unfit.”

After the funeral, my mother left him. She happened to find a small apartment adjoining the cemetery, and from her bedroom window she could see Roberta Lee’s gravestone. She’d sit there for hours, staring at the little granite block. My father kept calling. He said they should get together for a few drinks and talk. He said he needed her. Honest to God. She shouldn’t just throw his precious love away.

![]()

Saturday, December 31, 1955, 11:35 PM. I’m in the basement, gently tweaking the tuning knob of my short wave radio to keep the signal clear. The BBC has a program about Halldór Kiljan Laxness, who’d recently won the Nobel Prize for Literature. “When he was fourteen, Laxness published his first article in a newspaper,” the announcer says. “During his career he wrote fifty-one novels, poetry, plays, travelogues, and short stories.” I love the cultivated English accent of that announcer. It makes him sound like he knows exactly what he is talking about.

“Johnny!” my father calls from the head of the stairs.

“What?”

“Time for bed.”

Bed? That sounds odd, because this is New Year’s Eve. And what’s he doing still at home, anyway? Why isn’t he out there celebrating?

“I’m not ready for bed.”

“Get up here right now, or do I have to come down and get you?”

Oh, Christ.

We climb the stairs to the second floor. I go toward my room. He says, “You’re sleeping with me tonight.”

“What?”

“You heard what I said.”

“I’d rather sleep in my own bed.”

“Goddamnit, get in here. Now.”

I crawl into his bed, move to the far side, and turn my back to him. But he reaches over and pulls me close. He is so lonely. He needs so much to cuddle. To spoon. He needs me to make him feel better. I feel his groin pressing against my ass.

The window faces the street. I stare at the slats of the blind. And I wait. Then come the noisemakers, tooting horns, fireworks. “Happy New Year!” voices shout. “Happy New Year!” I hear all that, but then I don’t. By then I learned how to hear and feel nothing.

![]()

Monsignor Kasmirski and I sit on a bench in Crandall Park, at the edge of a large pond. Oaks and poplars rustle in the breeze. Canada geese spot us, and come swimming over.

“Understandably, your father is deeply distressed by your decision to go live with your mother, my son,” Monsignor says. “Your father truly loves you, and doesn’t want you to go away. When he spoke to me this morning tears were streaming down his face.”

I turn my head. I can see him bawling. I’ve seen it many times before.

“Have you considered the consequences of your decision?”

“Yes, Monsignor. I’ll be with my mother, and I’ll be happy.”

“But what about your father?”

“I could visit him.”

Monsignor reaches into a paper bag and tosses out pieces of stale bread. The geese waddle out of the water and lunge hungrily.

“Visit him? After such a profound betrayal?”

Face burning, I look downward and say nothing.

“You are at an important crossroads in your life, my son,” he says. “It’s unfortunate that you’re obliged to make such a grave decision, since you are still a child. But we do not choose the cross our Lord requires us to bear. We must accept it, without question. Now, I want you to think about this.”

“Yes, Monsignor.”

The holy man tells me there is but one moral choice. I must not go live with my mother, Elizabeth, but rather I must remain with my father, because that will keep me in this parish where I’ll continue my Catholic education. And at the appropriate time I’ll go on full scholarship to the Jesuit seminary, to study for the priesthood.

“You know how important that opportunity is, don’t you?”

“Yes, Monsignor.”

“You also know what Augustine teaches us: ‘The measure of loving God is to love him without measure.’ This means you must abandon everything, including a mother’s love.”

These Canada geese. All they care about are the bits of stale bread the holy man is tossing to them. For these birds, it’s sufficient nourishment.

Monsignor Kazmirski continues: “And on purely ethical grounds, well, you must consider the impact your decision to live with your mother would inevitably have—not just on yourself, but on others. How do you suppose your father will feel? Your aunt? Your uncle? Your cousins?”

I look at Monsignor. “It’s not like I’d be going to another country,” I say.

“But listen, my son. Your father nurtured you for nearly ten years. And to whom would you be going? Is it not to a woman who abandoned her husband and her infant son, and sought a divorce?”

I say nothing.

“Your mother’s acts were unquestionably immoral and sinful,” he says. “Which is why she was excommunicated.”

“But my father is a sinner, too.”

“We all are sinners,” Monsignor Kazmirski says quietly.

The sky darkens, the wind picks up. We head for the park’s exit. I have to walk quickly to keep up with Monsignor Kazmirski’s long steps.

“I want to live with my mother,” I say.

“Yes, you do. But you can not ignore the facts. Your mother made no attempt to communicate with you for nearly ten years. Unlike her, your father didn’t abandon you. True?”

“Yes, Monsignor. But . . .”

I can’t finish the sentence. I wish I could tell him about the zillions of cockroaches that scurry for cover when I turn on the kitchen light in that empty house. Or my father puking in the bathtub at three in the morning, because he can’t use the shit-clogged toilet. Or all those belt whippings he seems to love giving me.

“You need to think about this, “ Monsignor Kazmirski said. “But you know what you must do. In the name of God.”

The judge is bald, stately and plump. His rimless glasses reflect the bright light of the windows, so I can’t see his eyes. That big man with a fat neck does not smile, up there on his bench in the echoing, marble courtroom. My father and his lawyer sit at one table, and my mother and her lawyer are at the other.

“I can’t hear you, speak up,” the judge says, clearly annoyed.

“I said I want to live with my father.”

“That is your choice?”

I lower my head, look at my hands.

“Yes,” I whisper.

“Speak up!”

“I said YES.”

My mother’s lawyer says something I don’t understand. My father’s lawyer rises, and speaks for a while and I don’t understand him either. I can’t think, my brain is too numb. Then the judge cracks his gavel, a sharp explosive sound that startles me.

My father’s nostrils flare in triumph. He shakes his lawyer’s hand, and then he throws a hateful glare at my mother.

I have no recollection of what he says in the car on the way home. But I do remember clearly that he went out to celebrate after he dropped me off. I didn’t mind. I had the house to myself.

Late that evening in the darkness I’m lying on the living room couch. From the radio’s loudspeaker come the saccharine strains of Brahms’s “Lullaby.” Obscenely sweet. Utter pathos. Pathetic.

How could I not weep?

![]()

I open the drawer to the left of the sink. Surprised cockroaches scurry for cover. The old butcher knife lies alongside the greasy plastic tray that contains a rusty potato peeler, several ladles, a narrow spatula, spoons, forks, screwdrivers, pliers, and a dusty roll of black electrician’s tape. I sit down on the stool in the corner, and examine the knife.

The house is empty and silent, except for the hum of the refrigerator. The knife’s handle is cracked, its flat-headed brass rivets have long ago lost their sheen. The blade is narrow, eight or nine inches long. The steel is dark-colored, mottled. But it still has a point, and its edge is sharp.

Maybe my grandmother had used this knife to cut bread. There were lots of things in that house that she’d probably used. Big, dark blue speckled pots in the basement. A funny looking washing machine with an oversized wringer attachment.

She probably used this knife that time she lopped off the head of a live chicken she’d brought home from the farmer’s market. I was only about four or five years old, but yes, I remember her deft, decisive movement, the flash of the blade, the spurting of crimson, and that chicken running crazily across the basement floor, headless. Later came the smell of singed feathers, of the steam from boiling water.

I grasp the handle with both hands, hold the blade pointing toward my chest. I lightly rest the point on my sternum, and see myself falling forward, holding that knife in place so that on impact the floor will drive the blade home.

If I do it right, death will be quick. Won’t it? That’s the way it’s shown in the movies and on TV. When a guy gets stabbed in the chest he drops instantly, is dead before he hits the ground. A matter of seconds.

I am ready. Ready right now. I stand up.

Heavy pounding in my chest. Rapid shallow breaths, in and out. A tingling in my arms. A light-headedness, a nauseating sensation of things rushing along too quickly.

Now.

Go ahead.

DO it!

Honk of a horn out on the street. Rushing sound of tires. I raise my head.

Inside a house you can’t tell which way a car on the street is moving. The walls absorb and consolidate sound waves, thus masking all directional quality.

The sound of a moving vehicle is subject to physical laws, and involves the contraction and expansion of wave forms. An oncoming vehicle compresses the waves so that from a fixed position you hear the sound as rising in pitch, whereas an outgoing car’s motion rarefies waves so its pitch appears to be falling. The Doppler effect.

It’s EASY you fucking coward.

Just fall forward!

Now!

Pitch, intensity, and timbre are the three basic properties of sound. Pitch is expressed as the number of Hz, or cycles per second. On a saxophone the note A above middle C is 440 Hz. Doubling the frequency produces a note an octave higher; halving the frequency renders a note an octave lower. Sound travels at about 1,100 feet a second.

I look down at the knife.

Another car drives by on the street in front of the house.

Yes, everything is held together by the immutable laws of physics. The sound produced by a moving car remains at a constant pitch, excluding of course the variations brought on by increases or decreases in the engine’s rpms. It’s all a matter of relativity, point of view.

Ah, fuck it.

I walk over, put the knife back in the drawer.

The pounding in my chest diminishes. I breathe easier, deeper. I lock my fingers, push outward. The bones pop satisfactorily. I yawn. Blink.

There are other examples of relativity. For instance, if you’re riding your bike in a shower the falling rain strikes your face at an angle governed by the speed you are traveling. But for a person you pass, who is standing still on a curb, the rain is falling straight down. Your forward movement creates the angle.

As soon as you stop moving, well, the rain again falls straight down.

Which it had been doing all along.

![]()

My father and I were in the kitchen. He’d just come in pretty loaded, even though it was only six in the evening. He owed me fifty dollars for working in his tuxedo rental shop during the summer. I asked him to please give me the money because I wanted to buy some stuff before I left for Air Force boot camp.

“I ain’t giving you shit,” he slurred.

I’d done a good job for him. I did every single thing he wanted me to do, and he knew it, because he repeatedly checked my work, as if he needed to find something wrong with it.

“Come on. You owe me the money.”

“What’s the matter, are you fucking deaf? I said I ain’t giving you shit.”

“Why?”

He gave me an intense glare of disgust. The man was just full of it, literally overflowing with anger, resentment, and hatred.

“I don’t have to give you a reason. Now get your skinny ass the fuck out of here.”

“You owe me the money,” I said.

He grabbed the big glass ashtray on the table, and in a clumsy drunken motion hurled it at me. I quickly moved my head to the side; the ashtray lightly grazed my cheek, bounced off the wall, and rattled along the floor. It didn’t break. I turned. He staggered toward me.

I seized his shoulders and slammed him, hard, against the kitchen sink’s cabinet. He was as light as a bird. The muscles of his arms were flaccid, mushy. I’d expected great resistance, strength. But he had virtually no substance. So this is what terrified me all those years?

He got up and lunged toward me again. And again, I grabbed him by his arms and this time threw him even harder against the cabinet. He fell to the floor. He drew up his knees, and groaned.

Trembling, I kneel beside him and put my face close to his. I say the words slowly and clearly: “If you ever raise your hand to me again, motherfucker, I’ll kill you.”

I heard later that I’d broken four of his ribs. He was in the hospital for a few days, then they sent him home. No, I didn’t get any satisfaction out of my violent act. It took me a couple decades to get over the trauma of that symbolic patricide. All I ever wanted from him was to stop hurting me.

Was that too much to ask?

![]()

In the middle of the night my father would stagger up the steps, and come into my bedroom. With a sigh he’d sit down and begin mumbling: “I love ya, Johnny. Honest to God, I love ya.”

He wept as he repeated those words over and over again. Then he’d bend down to kiss me and I’d smell his stench of booze, cigarettes, vomit and foul underarm sweat.

“I love ya, Johnny. I mean it. I wish things were better. Honest to God.”

Even as a child I saw it for what it was: puerile sentimental bullshit. Drunk talk. If he loved me so much, why did he glare at me all the time, even when he was sober? Why did he make it so clear that he wished I had never been born?

And those whippings.

He’d pull off his belt in a quick motion, and he’d grip my shirt collar, and I’d squirm, trying so hard to avoid the biting sting of that whistling strip of hard leather. The more he hit me, the more he wanted to. Like a frenzy. His rage seemed limitless.

When I was about fifteen he got pissed at something I’d done or said, and grabbed me. I don’t know why, but suddenly my fear vanished. I just stood still. I did not try to avoid the blows. He lashed out two, three, four times, on my back and buttocks, but I just stood there silently.

He’d never experienced such a thing before. His victim no longer squirming, fighting, bawling, trying so desperately to escape. In that silent state I no longer felt any pain.

He stopped, belt dangling at his side, and stared at me, uncomprehendingly. I turned my head and said, “Are you through?”

The poor guy didn’t know what to say. But from then on, whenever he got angry and reached for his buckle, he’d suddenly remember that scary episode and stopped.

Shortly after I was born he’d set up some sort of savings account for my college tuition. But he stopped talking about it by the time I turned ten. In my senior year in high school, everybody was thumbing through college catalogs, trying to figure out where to go. These kids were talking to their parents about it, obviously.

But I knew that such talk was impossible with my father. He didn’t want to hear anything about what I wanted, or needed. He’d get angry when I showed him my shoes with run-down heels, or my underwear in shreds, or my jeans with holes revealing both of my bony knees. He made me feel as if I were asking for something extravagant or unnecessary, or that all I could ever think about was MYSELF. As if wanting shoes or decent clothes was criminal.

So the issue of college—or indeed what I would do when I graduated high school—was for several weeks just up in the air, unresolved. He made it clear that he never wanted to talk about these things. And that was it. So what was I supposed to do?

Well, I finally decided we had to talk. With a grim look and a long sigh, he sat down on the couch. “Listen, Dad,” I said, “I need to know if you are going to pay for my college. Or what.”

He slowly shook his head. “No,” he said.

“Why?”

“You wanna know why?”

“Yes. Tell me.”

“Because you ain’t got it in ya.”

When he said that, I recalled the thing he told me a couple years earlier in a sudden fit of candor. “You know all those A’s you got at St. Xavier’s?”

I nodded. “Yes.”

“Well I always thought the nuns gave you those good grades because they felt sorry for you, coming from a broken home.”

You ain’t got it in ya.

Well, all right, I thought. I’ll just go to Plan B, which was enlisting in the Air Force. Down at the recruiting office in the Post Office building I’d taken an aptitude exam, so they could decide which career field to put me in. The sergeant said that I’d gotten the highest score ever recorded.

So I said sign me up, sir. He replied that since I was still only seventeen I’d have to get parental permission.

“What the fuck is this?” my father wanted to know.

“It’s an Air Force parental consent form.”

“I ain’t signing it.”

“What?”

“I said, I ain’t signing it.”

I paused three seconds. Then I heard myself saying, “Sign it or not, I don’t care. But I’m leaving, one way or another.”

He signed.

![]()

In late August 1959, in boot camp at Lackland Air Force Base in Texas, I came in first on the obstacle course, beating out all the muscle-bound jocks. Me, the skinny runt, showing up those ex-high school football players! They finally came staggering across the finish line, huffing and puffing, and dropped to the ground, exhausted. I stood in triumph, basking in the glow of approval on the drill sergeant’s face. “Airman Palcewski obviously has more desire than any of you lazy assholes,” he said.

After graduation they sent me to the Air Force Intelligence School at a base outside Wichita Falls. In eight months I learned how to select enemy targets by examining aerial reconnaissance photographs. I was the best in my class. Along the way I won a case of beer for correctly identifying a strange looking building that had what looked like a racetrack on its top. It was an automobile construction plant in Munich, Germany, where they ran tests of the vehicles on the roof. I’d read about it earlier, in an issue of Popular Science magazine.

My first duty assignment was at a Strategic Air Command base near Amarillo, Texas. The 4128th Strategic Wing had a couple dozen B-52 bombers loaded with nuclear weapons, always on standby, ready to destroy the USSR and China in the event of WWIII. This awesome nuclear arsenal was the embodiment of the early 60s’ geopolitical theory of Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD), designed to prevent major war, and—amazing to say—it succeeded.

My job was to assist Intelligence Officers prepare “navigators’ combat mission folders,” which were very much like the handy little road trip planners the American Automobile Association used to make for its members. The folders contained detailed aeronautical charts that showed the way from Amarillo to Vladivostok, Peking, and other major targets in Russia and China. They also included my specialty— “artwork radar predictions,” which were my carefully hand-drawn simulations of what targets would look like on a B-52 navigator’s radar screen when the plane got there.

I won a commendation from SAC headquarters in Omaha for devising a simple way of making a complicated calculation involving radar images, which new calculation saved the Air Force millions of dollars worth of man-hours each year. At an awards ceremony attended by all personnel, Wing Commander Colonel Cridland handed me a $50 savings bond and a nice certificate, suitable for framing. A photographer took a picture of the presentation, which appeared in the base newspaper.

In the winter of 1961, I took leave and got a hop on a C-47 to Youngstown. My mother wept when she saw me, all spiffed out in my elegant blue uniform. She was so proud of me! “Ah, what a fine young airman!” she said. So did my uncle Jack, her brother, a former Navy lieutenant.

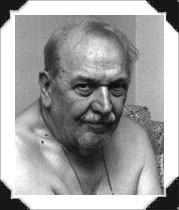

I found my father sitting hunched over a drink at the bar in the Mahoning Valley Chapter of the Polish League of American Veterans. What did I expect from him? I suppose I thought he’d smile broadly, and congratulate me for my achievement. But he turned, and blinked, like he just couldn’t comprehend what had suddenly appeared before him. He wasn’t interested in my telling him of my adventures in Strategic Air Command Intelligence, nor anything else along those lines. It was clear from the look on his drunken face that he believed I was making it all up.

![]()

Whenever my computer breaks down, as it regularly does, I get a flash of mild anxiety because it represents a loss of control. Sudden noises do the same thing.

This neurosis comes from one night when I was awakened by my father whipping me with his belt. I’d run away earlier that day, and he couldn’t find me, and I guess he’d been out looking for me for a long time. His furious drunken assault confused then terrified me.

I suppose my aunt Jane had chewed him out, humiliated him in front of others. “What’s the matter with you, Chester?” she asked. “Why can’t you keep track of your own son?”

Of course she didn’t bother to ask him why little Johnny had run away. Could it be that the child just can’t bear any more of his whippings?

![]()

My cousin, Albert Hoffman, once told me: “Johnny, when you were a kid you were a sissy.”

Well, why was I a sissy? And why aren’t I one now?

You might call a whipped dog a sissy. He grovels, he whimpers, he pees on the floor, he’s afraid of his shadow, because he knows his master at any moment will whip him again. He’s on a leash, he can’t run. The only effective strategy—the only one at his disposal—is to belly up in submission. His instincts tell him that if he does this in the presence of the Alpha Male, well, he just might get off. If he’s lucky.

The allegory breaks down because my father was never a true Alpha Male. He attacked only women and children. He didn’t have the balls to take on another man, who wouldn’t hesitate to kick his sorry cowardly ass.

I’ve often wondered: Why was my mother so drawn to that needy and perpetually angry man? Why didn’t she dump him when she had the chance? But of course that line of thought leads to the existential realization if she had indeed walked away, I wouldn’t be sitting here right now, pissing and moaning.

My father was the biggest mistake in her life. And in my father’s glaring eyes I was the only mistake. But my mother made it clear to me I wasn’t. “I’ll always love you,” she said.

I look through this pile of old photographs. Most of them are of an extraordinarily beautiful little girl surrounded by parents and relatives who literally shower her with adoration, affection, affirmation. I hear their laughter, and my uncle Jack’s flawless pitch-perfect tenor voice at the piano, singing Deirdre of the Sorrows. And I think, Christ, what a pity she allowed my father to poison her life the way he did.

But then at least she had the good fortune to find a real man in Bully, who honored his commitment to her to the very end. When she sunk into the blackness of dementia, he stood by her. He refused to put her in a nursing home, as everyone told him he ought to do. No, he just went about the daily business of changing her diapers, cleaning her dirty sheets, bathing her, dressing her, feeding her. He didn’t find excuses, he didn’t run.

During my last visit to Youngstown I sat down and made sure Bully understood how much I admired him for that. “The plain fact is,” I said, “If I found myself in your shoes I don’t think I could do it.”

I didn’t go to my mother’s funeral, or to his a couple months later. Not out of disrespect for their memory, but rather because—thank God—we’d already made peace. We had no unspoken words, no unfinished business between us.

![]()

My grandmother Edna, a hard-drinking and headstrong Irishwoman, told me many times I was her favorite little boy, because we were exactly alike. The story was that in the early 1900s she gave up her vaudeville singing & dancing career and got married in Ohio to one Frank Joyce, whose ancestors lived in a small village in the Maum Valley, to the west of Lough Mask in the northern part of County Galway, Ireland.

She liked to say that she was just the latest in an unbroken line of rogues and criminals. Her grandfather, Jack, for instance. During the Great Famine he was convicted of sheep stealing and subsequently transported from Dublin to a penal colony in New South Wales, Australia.

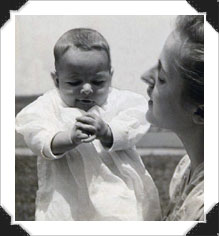

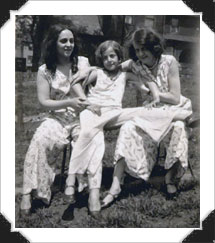

Edna may have left vaudeville, but she never gave up singing, dancing, smoking, and drinking. She did what she pleased. Always. Frank thought that once his wild wife gave birth to baby Jack, and then Betty, she’d settle down. Not a chance. Look at the picture. It’s Edna and her daughter Betty, my mother, at the Avalon Ballroom in Youngstown, Ohio, having a good time. Frank is at home, with the dog, listening to the radio play-by-play of the Cleveland Indians game.

I’ve always liked being a direct descendant of an Irish sheep stealer and a vaudeville trooper. It’s an interesting story. And, more important, this history provides all the explanations and excuses I ever need for my own outrageous behavior.

After all, it’s in my blood. Right?

![]()

July 23, 1998

Hello, it’s me. I’ve been thinking that I’m getting older. And so are you. There’s a lot of unfinished business between us, so maybe we ought to try to sort it out while we still have a chance. I think a good way to start would be for you to write me a long letter. About you and my mother, all the stuff that led to your separation, divorce. My sister Roberta. You’ve never talked to me about any of this, so maybe after all these years it’s time. The whole truth.

If you don’t want to do this, well, then this is my final good bye to you. I wish you the best.

John

So I wrote it out in longhand, in black fountain pen ink on a sheet of good bond paper. I didn’t type the words because I thought they’d appear even more impersonal than they already were. Folded the single sheet in thirds, put it in an envelope. Wrote his name and address on the front of the envelope in block draftsman’s letters, affixed sufficient postage. Opened the front door, but saw it was raining. I put the envelope in a plastic zip-lock bag and walked it over to the mailbox, five blocks away.

One time I said to my father: “Let’s talk, okay?”

And he squinted, as he always did when he was drunk. “Talk? You wanna talk? Okay. What do ya wanna talk about, huh? Come on. Tell me.”

I wanted him to tell me the whole story of how I came to be. And why my mother left him. She’d already told me her version, so it was only fair that I give him an opportunity to tell me his.

For Christ’s sake, dad, give me an identity. Tell me I have a good reason to be here, that I belong. Tell me that between you and my mother there came something of value. Tell me about your father, what you felt about him, how he treated you. Give me a history, some sense of family origin. As it is, I have nothing. I’m fucking empty. I don’t belong anywhere.

He shook his head. No way. Now get lost.

![]()

On the 7th of July 1970, in the maternity ward of Lenox Hill Hospital on Park Avenue in Manhattan, I witnessed the birth of my daughter, Lara. She emerged bright-eyed, fully alert. I held her in my arms briefly before they wrapped her up in a white blanket and put her into an incubator. My little daughter appeared to be fascinated by everything around her in that brightly lit room. Those big, beautiful eyes of hers went from one thing to another.

Half an hour later I made two telephone calls. First one to my father.

“Congratulations,” I said. “You’re a grandfather.”

I went on to describe what I had just seen. A miracle. No words can really describe it. You know?

“I have good news too,” he said.

“Oh?”

“Yeah. I just bought a new car.”

And then I called my mother.

“Congratulations,” I said. “You’re a grandmother.”

She wanted to hear more. And more. About how Lara looked, how much she weighed, and so on.

“So when are you coming to see her?” I asked.

I heard a gasp. “You mean after all those terrible things I’ve done you still want me to visit?”

“Listen, I keep telling you, it’s all water under the bridge. Of course I want you to come.”

My mother was in our apartment on West 83rd Street four days later. I told her she could stay as long as she wanted. We had plenty of room.

In 1982, well into a solid career as a corporate magazine editor, photojournalist and literary fiction writer, I decided that I needed to go back to college and get my degree. I figured that given my intellectual pretensions, I ought to have a piece of paper to back them up.

Four years later I sent out invitations to everyone I knew. At the conclusion of my graduation ceremony, with a diploma in my hand, I strolled across the lawn in front of the library. And to my astonishment, there he stood. My father. It was a most awkward conversation.

“When did you arrive?” I asked.

“I was at that baccalaureate service in the church yesterday,” he said.

“Oh? I didn’t see you,” I said.

He looked me up and down.

“You know, you look like a little kid in that outfit,” he said.

A little kid? I was forty-four years old. And that outfit included a big, shiny medal on a silver chain, which I’d just received for being inducted in Alpha Sigma Lambda, the national honor society for continuing education students.

“Hey,” he said, “we oughta get together for a few drinks tonight, huh?”

“As it happens,” I quickly replied, “I’ve already made plans. You should have called to let me know you were coming.”

I wasn’t about to let him spoil this important day. No way in hell. But nevertheless he didn’t look at all disappointed. I suppose that was because he knew he’d have those drinks whether I went with him or not.

“Oh, okay,” he said. “Maybe some other time.”

“Sure,” I said.

That was the last time I saw him.

![]()

In mid-January, 2005, the phone rang. My girlfriend, Maria, said she’d just called my father. I asked her why.

“Because,” she replied, “I thought if I got to know him I might understand you better.”

But the woman who answered Maria’s call said she could not bring Chester to the phone, because he’d passed away five months ago.

“What?” Maria said.

“He died,” the woman replied angrily, and she spelled out the word. “D. I. E. D.” Then she hung up.

I went to the web and checked the obits in the Youngstown Vindicator. Yes, Chester Palcewski’s death suddenly occurred the morning of August 22, 2005. And, “. . . he will be sadly missed by all who knew and loved him.”

I’m not among those in the list of his survivors. Nor are Lara and Stephen, my children, his grandchildren.

Chester Palcewski, 89

AUSTINTOWN. Chester Palcewski, 89, passed away unexpectedly Monday morning [August 22, 2005] at his home. He will be sadly missed by all who knew and loved him.

Chester was born Feb. 20, 1916 in Youngstown, a son of the late Casimir and Josephine Hoffman Palcewski, and was a lifelong area resident.

He attended The Rayen School and served in the U.S. Army during WWII.

A tailor by trade, Chester owned and operated Bouquet Tuxedo Rentals on Mahoning Avenue in Youngstown for many years and also worked at Masters Tuxedo Rentals. He was a member of the Nativity of Christ Orthodox Church and PLAV Post No. 87.

He leaves his wife, Anne Stefanoski Miladore Palcewski, whom he married Nov. 1, 1966; four stepchildren, Joann (the late John Jr.) Panko of Palentine, Ill., Sandra (Frank) Burkosky of Solon, Elaine (Richard) Luchansky of Pawleys Island, S.C. and Nicholas (Donna) Miladore of Boardman; nine grandchildren; and 11 great-grandchildren.

A brother, Alex, and a sister, Jane Hubler, are deceased.

Family and friends may call from 5 to 8 p.m. Friday at Kinnick Funeral Home, 477 N. Meridian Road in Youngstown, and from 9:30 to 10 a.m. Saturday at Nativity of Christ Church.

A prayer service will be held at 7 p.m. Friday at the funeral home and funeral services will be held at 10 a.m. Saturday at the church.

Interment will take place at Lake Park Cemetery.

![]()

Two photos by John Palcewski appeared in Archipelago, Vol. 6, No. 1.

Write to us: