| PALEOGRAPHICS: EARLY CABBAGE

STELLA SNEAD

In the late and somewhat preposterous years of the 20th century, a curious

and highly unexpected discovery was made which caused a goodly amount of scholarly

speculation and some shimmering delight in a certain few.

These few are not well-known, not the leaders of our faltering western

civilization who constantly bum their way around the world, spreading its catchy but less

salubrious aspects. These aggressors are not necessarily politicians, traders, technical

advisers or even do-gooders. Some are bold and forthright travellers seeking to burrow

into the remaining crevasses of those societies still enduring, although quietly

disintegrating, in remotest jungle or desert. And now fast upon the traveller’s

disappearing heels come the ubiquitous tourists, blandly thoughtless, exuberantly

acquisitive. They want to take it all home: red mud in the hair, bones through the

nostrils and ears, paint on bodies, patterned gashes in flesh, the often beautiful but

weirdly uncomfortable clothes and jewellery. They wallow delightedly; they do of course

acquire objects, but mainly it’s photographs. In a horde of fifty or even only

twenty, there will be no more than two or three safari-suited bodies not slung with

cameras and lenses. These often inexperienced paparazzi angle, contrive, and snap, or let

us say shoot -- if they are even mildly professional.

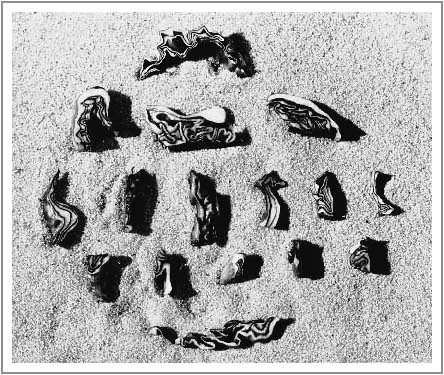

FIG. 1 - EARLY CABBAGE (S.S.)

Oddly enough it was two of these most casual world prowlers who

unwittingly brought back the first intimations of the above-mentioned discovery. It

consisted of a single, rather blurry, photograph of what appeared to be ancient script.

This first tantalizing piece of evidence came to light some twenty-five years ago, say in

the mid- or late 1960s, and was taken during the wanderings of a feckless pair of hippies,

neither of whom could remember which of them had snapped the shutter, or where. It seems

they paced the world in a leisurely manner and with a meager cash flow for a number of

years. They seldom looked for anything in particular, their only plan being to move from

one place to the next. This they certainly did. Starting in the Balkans, they covered much

of the Middle East, parts of Central Asia, India, Nepal, and Indonesia, finally coming to

rest in Australia: the wife with child, the husband with a job, their photographs still in

an uncatalogued jumble. In the fullness of time they gave the script photo to an Afghani

student who later specialized in the decipherment of arcane languages; he brought it to a

University in India where he showed it to a colleague. They were both mightily intrigued

but thoroughly baffled. Whenever anyone in their field visited the university -- if

considered worthy and sufficiently erudite -- he or she was consulted. Unfortunately the

results only yielded a further accumulation of puzzled scholars.

Over the years the original two-degree-laden fellows never forgot their

joint enigma for very long. After they both became full professors and had more

opportunities to travel, they carried with them the by now rather over-examined

photograph. Once it was to a Conference of Cryptologists in Khiva, a desert city not

usually visited by outsiders, in the Russian Uzbekisthan. Later they spoke of their find

at the well-attended meeting of the Mongolian Branch of the society of Advanced

Scriptorial Studies in Ulan Bator. At the latter, in particular, many fervid and sometimes

bitter arguments took place; but never was there a ghost of a solution. Two of the most

illustrious and venerable of these savants died admitting ignorance; others retired; but

the two original discoverers kept up the grueling search. They labored through many a

hidden library, and in the dusty scriptoria of far-flung monasteries where the books were

unbound, printed by hand, and (often) wrapped in cloth. They looked at characters written

on silk, on tablets of stone or baked clay, on woodbark or palm leaf, on papyrus or

parchment. They found nothing even, in consolation, approximating what they longed to

find, and were saddened, for they too were getting old.

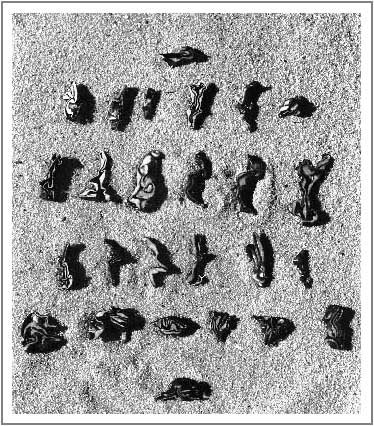

FIG. 2 - EARLY CABBAGE (S.S.)

Then one day a young American traveling in India searched them out. He was about the

age they were when, so many years ago, their quest had started. He was employed, he said,

as an apprentice assistant in the Photographic Archive of the Sackler Gallery in

Washington, D.C. He told his eager audience that the Museum had been gratified to accept a

collection of photographs, negatives and transparencies at the death of the photographer,

a widely-traveled English woman who had specialized in picturing the Orient. “While

sorting and cataloguing this large and diversified mass of material,” said the young

man, “I came across these” -- and he spread before them a set of stunning

black-and-white prints of the very script they had been trying to trace for over thirty

years. The two professors were suitably dazzled; nay, they were ecstatic and at the same

time tongue-tied. Then in a few minutes questions leapt from their lips, those intensely

earnest queries of scholars nearing a breakthrough. But still, even now, there was no

solution, and slowly the two gentlemen slumped in their chairs. The photographs showed the

images but gave no clues as to when, how or where they had been obtained. On their back,

on the upper right-hand side, was nothing but a string of numbers and letters: which were,

decided the Archive Department, merely a code indicating what the photographer had done

under the enlarger. Ruffling through them once again, the budding archivist turned up one

print bearing two words in faded pencil, “Early Cabbage”.

There followed a deeply-dejected silence, until the Indian professor all but screamed,

“This is the most brazen cruelty to scholars and researchers ever committed!”

Stunned perhaps, his Afghani colleague slowly roused himself: “We won’t give

up,” he announced calmly. “We must raise funds and go to New York where this

infuriating lady recently died. We must interview everyone we can find who knew her.”

Then with some urgency he added, “We must hurry to find these people before they also

die, and before we do.” Their eyes shone for a few moments as they looked at each

other, then slowed dimmed, as did the sun’s evening light in that university study.

“It could all be a dastardly hoax,” said one of them.

_______________

©Stella Snead, 1997, story and photographs.

|