|

c h r o n o l o g y

| 1910 |

Born London, England. (See “Early

Childhood and Before”) |

| 1915 |

With mother, Hettie (vegetarian cook-housekeeper) run away

from mentally troubled and beginning-to-be dangerous father. |

| 1916 |

Settle in Leicester (Midlands) first in vegetarian santarium,

later in own house until I was eighteen.

Education: At first, scattered village schools |

| 1917-24 |

Proper/snob girls day school. |

| 1924-27 |

Progressive, co-ed, self-governing, Theosophical, vegetarian

boarding school St. Christopher’s, Letchworth, Herts., England. |

| 1927 |

Last three months of year, stay with French family in Paris,

meet first Americans, attend Alliance Française, meet almost every other nationality

– a heady experience for someone confined until then to England only and also

confined to a background based mainly on vegetarianism. I was nevertheless entranced by

Paris although I knew nothing of the special and extraordinary people who made it the

place to be in these, the golden years, the ’20s & ’30s. |

| 1928 |

Move from Leicester to Sutton, Surrey (edge of London).

Secretarial course in London. |

| 1929 |

Have own car. No need to earn a living. Try this, that and

the other. No satisfaction, lonely, bored. During my early twenties, deep depressions

started to descend, self-pitying they were, and would hang around for months. I cried a

lot, wanted to hibernate like the bears or to be very old or dead. Eventually would come a

day when I would zoom up and out of it, like a kite caught by the wind though the outside

conditions were exactly the same. So what was this? It must be connected with my father,

inherited perhaps. My mother was sympathetic but she had no clear idea, it seemed, though

she had lived with someone much worse afflicted for fourteen years. Neither of us knew

much about psychiatry. |

| 1936 |

And so it went on,just one long slow-moving waste of time,

until in May ’36, I was with my one and only artist friend on the Spanish island of

Teneriffe. We had access to a delectable private garden where she was painting flowers

using oils. I watched her closely one day and had a strong and immediate conviction that I

could do this, at least I could do what she was doing –

applying the oil paint neatly with a brush and it stayed where she put it, quietly and

obediently. That appealed to me. I did not have to be quick and dexterous as with

watercolor and some other skills. Luckily we had a garden at home with some of the subject

matter I needed. I painted in my bedroom for the rest of the summer. My mother was

somewhat disturbed; I was taking no exercise, neglecting friends, hardly using my car

even. Come September there were three choices open to me. My painter friend had the

offer of a house in Tangier, or I could just stay home and paint without tuition, or I

could study with the French painter Amédée Ozenfant, who was coming from Paris to open a

school in London. Of course I had not heard of him, but the idea of one teacher and a

small number of students appealed to me far more than one of the big schools, so I chose

this, rather tentatively, for one semester. I now heard that Ozenfant was a friend and

colleague of Léger and that they had taught at the Académie Moderne in Paris, that Le

Corbusier had built Ozenfant a house, and that together they had started the Purist

Movement. The Ozenfant Academy of Fine Art opened in London in mid-September ’36.

By then, I had done six small flower paintings. I took them along and said nothing. This apparently

was the right thing to have done; teachers like beginners. There was one other student in

the nicely spacious studio: she was Leonora Carrington at nineteen, beautiful, her eyes

intense and mischievous. What people! I had never met anyone remotely like them. Other

students soon joined us. Against the back wall was an immense mural-sized painting on

which Ozenfant was still working; I was doubtful if I liked it. The main thing was that I

was enthralled by meeting so many people in the arts and to have found for myself a

passion at last. This apparently

was the right thing to have done; teachers like beginners. There was one other student in

the nicely spacious studio: she was Leonora Carrington at nineteen, beautiful, her eyes

intense and mischievous. What people! I had never met anyone remotely like them. Other

students soon joined us. Against the back wall was an immense mural-sized painting on

which Ozenfant was still working; I was doubtful if I liked it. The main thing was that I

was enthralled by meeting so many people in the arts and to have found for myself a

passion at last.

And it was such an absorbing passion; although I was to have depressions for many years

to come, I don’t think I was ever bored again. Leonora stayed two or three months,

met Max Ernst, went to live with him in France. I went on to study with Ozenfant for three

years in London, then for two more years in New York. |

| 1937 |

I was often shy in the studio as I knew so much less than

anybody else. The model took the same pose every day for two weeks, and we drew on

double-elephant sized paper meticulously stretched onto a board. We could attempt the

whole figure or any detail of our choice. We used well-sharpened charcoal pencils,

building slow compositions with small ticks and much thought, no dashing quick sketches

allowed. It was probably a unique method not happening elsewhere (in any other school). It

suited me. I began to be a favorite student. I think, though I was not conscious of it at

the time, that it was this Ozenfant method of working that freed me to boldly decide that

I wanted to be a painter more than anything else, regardless of my lack of facility in

drawing. We students often spent Saturdays in the museums, for me one continual

revelation. At first I was most attracted to Gauguin and to Le Douanier Rousseau. Around

this time, I decided to do a painting at home, as I was in no way confident enough to do

it with others looking on. It was of a woman, naked, sitting cross-legged on the ground;

on either side of her a short distance away sat a cat; stretched across the foreground was

a snake; in the background, Rousseau took over: it was all fat, highly-indented leaves.

When I brought it to the studio there was a hush at first and then Ozenfant kissed me.

For some time now, I had wanted to get to America. I really wanted to emigrate, as I

had the over-exaggerated notion that if the Nazis should win the coming war it would be

the end of civilization in Europe. I believed all those in the fields of culture, that is,

all kinds of artists, teachers, philosophers, writers, poets, musicians, and scientists,

should make for the New World. I talked to the other students, wanted to tell Ozenfant;

but who was I to tell him what to do? |

| 1938 |

Ozenfant invited to give a summer course in Seattle,

Washington, U.S.A. Henry Moore came to the studio to teach us for a semester; a rewarding

period but also disturbing, because of the Munich crisis – we

were close to war and the possibility that Ozenfant might not return. I was perturbed as

it seemed so important to continue studying with him. But return he did, and with the

great decision to move the Ozenfant Academy of Fine Arts to New York, just as I hoped he

would. |

| 1939 |

World War II declared in Europe. I leave mother and lover and

board ship for New York, taking more books and reproductions of art than clothes. Start

work immediately and continue with Ozenfant for another two years. |

| 1940 |

August – my first journey across

the U.S. to California. The further west we went, the more exhilarated I was by the

bigness of the country, especially the desert-like Southwest, parts of which were still to

be explored and mapped! Returned in October to New York. Knowing something of what was

behind and beyond N.Y.C. made me feel more at home and content to be in this most

stimulating of cities (& this still holds). But the atmosphere in the studio had

changed; Ozenfant was less friendly and I was having money troubles; my allowance from my

ever-generous mother could not be sent out of England. |

| 1941 |

Early in the year when funds and hopes were at

their lowest came a telephone call from a millionairess, the result of a complicated

labyrinth of connections. She invited me to lunch and said she would be glad to lend me

money for the rest of the war. Miracle! I could go on working with Ozenfant, though it was

not to be for much longer. I left in May, feeling glad, and also capable, to be on my own.

At this time, refugees from all over Europe were flooding into America; in particular,

many of the Paris Surréalistes came to New York. Even though I was not part of this group

and had not done anything consciously surrealist, they were among the artists that

interested me most. I went to a few of their parties; at one requiring fanciful dress I

wore a handsome tail of greenish-black cock feathers, and one Xmas I hid small bells in my

poodle-cut curls. Earlier in the year, Leonora Carrington and I had most surprisingly run

into each other on the N. Y. subway just a week after she arrived from Europe. For those

several months, we met regularly. In the fall I was to have my first solo show as a

painter at a gallery on East 56th Street. On an impulse, knowing Max

Ernst was likely to come, I worked days and into the nights to produce a small surrealist

painting; there was another painting inspired by the Southwest that Max liked better.

Ozenfant also came, bringing his present students, friendly this time and full of praise

for this ex-student who had worked with him five years and followed him from England to

America! In December, suddenly -- it seemed nobody was prepared for

this-- Japan attacked the American naval base at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii. This drove

America into the war, thus coming to the help of Britain, the only country in Europe still

openly resisting Hitler. |

| No. 10 Gallery19 E. 56th St. |

| 1942 |

I now had friends in California, most of them refugees from

Middle Europe settled in Hollywood. During the summer I set forth again by bus, my

favorite vehicle for long-distance travel, especially in a front seat. I was eager to know

more about the Southwest, the interior away from the main roads. We were on the old Route

66 in northern Arizona, on the edge of the Painted Desert and the Navaho reservation. In

Holbrook, a tiny town, I got off the bus and went to a small hotel. The woman at the desk

told me how to travel in wartime America (gasoline was the only commodity rationed here):

Go to the Post office, the woman said, find out when and where the mail truck is going.

The driver would likely take me for a couple of dollars or nothing. These men were

responsible local people who knew the white traders to the Indians and the country. And

they went to remote areas, usually staying one night – no

hotels, but I could stay with the trader or a school teacher. At this time, these were the

first traders to the Navaho and the Hopi, and what trading posts they looked after! Full

of the splendid jewellery and rugs the Indians still made. Most of the jewelry they wore

themselves, the women in velvet covered with silver buttons and brooches, the men

sometimes wearing three huge concho belts at once, silver hat bands on their sombreros,

satin shirts in deep, shining colors. This part of the country was so recently occupied

by outsiders; Arizona only became part of the United States in 1912 –

two years after I was born. Many of the people I was meeting then were the first of their

kind in the West. For instance, John Weatherall was the first white man to find the

Rainbow Bridge, the largest natural arch in the world. I stayed with him and his wife at

Kayenta, just to the south of the now famous Monument Valley where Goulding was its first

trader. Lorenzo Hubble, one of the most legendary of them all, had only just died; in

fact, the woman in the Holbrook hotel had been his nurse, and I will always be grateful to

her, for she guided me to one of the greatest trading posts ever.

Finally, I got back on a Greyhound bus and continued the rest of the journey to

Hollywood, and settled down to painting. I was finding my own style; I had a new lover and

was full of ideas. Many of the paintings I saw whole just there in front of me. I ignored

Hollywood, but I had a Victory garden which I walked to – I

didn’t have a car. I grew melons, peppers, eggplant and the best green beans

I’ve ever eaten. I took a first aid course and thought often of England, even of

going back. My mother was more or less safe in a remote vegetarian guest house and did not

want me to face the high seas and the U-boats. We wrote to each other every week. |

| 1943 |

Painting was going well. I took a brief job as

a waitress at the hotel on top of Mt. Wilson; I was having a painterly interest in

astronomy, and up there was then the largest telescope, the 100-inch, but it was closed to

the public during the war. I penetrated a little, met some of the astronomers; seeing the

Hercules Cluster through one of the smaller telescopes was breathtaking: I had never felt

space so completely. Mt. Wilson was an inspiring place in several ways; if you were lucky

you could see the sun set and the moon rise, so big and with a reddish glow, facing each

other. The coyotes howled like wolves. I was warned not to wander too far, as there were

also mountain lions. Painting was going well. I took a brief job as

a waitress at the hotel on top of Mt. Wilson; I was having a painterly interest in

astronomy, and up there was then the largest telescope, the 100-inch, but it was closed to

the public during the war. I penetrated a little, met some of the astronomers; seeing the

Hercules Cluster through one of the smaller telescopes was breathtaking: I had never felt

space so completely. Mt. Wilson was an inspiring place in several ways; if you were lucky

you could see the sun set and the moon rise, so big and with a reddish glow, facing each

other. The coyotes howled like wolves. I was warned not to wander too far, as there were

also mountain lions. |

| 1944 |

First visit to Mexico. The main idea was to see the

newly-erupted volcano, Paracutín. As I was nearly a year late, it was almost dormant, but

I stayed on though I did not really like Mexico at first. There was a feeling of evil, and

I was appalled by the cruelty embodied in much of the pre-Colombian art. At the same time

it was an appealing country, underpopulated as compared with now. I have returned

frequently, into the early ’80s. For some time the British Isles had been filling

with American troops and the equipment of war, for the invasion of Nazi-controlled Europe.

In far-away California we knew little, as plans were secret until it happened, and that

was in June 1944. The end of the war was now predictable, but no one

knew when. I returned to New York

with many paintings, as the first step towards London, where I would go to see my mother.

Although I had been away from New York and other painters for most of two years, my work

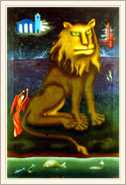

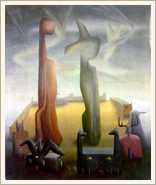

since 1943 had taken a jump towards fantasy. Animals were represented rather more often

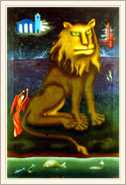

than people, e.g. “The Sulky Lion”: hardly more than two-dimensional, the

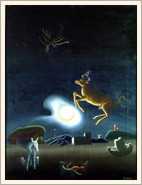

buildings small and quite out of scale. “Tiger in the Sky”: similar, but more

three-dimensional; and from then on, distances increased, by ’43 giving the sense of

a place where you and the viewer might be. This is one of the characteristics I like about

Surrealism. It was also in the early ’40s that certain American Abstract painters

were gathering in New York. William Baziotes was the only one whose early work really

pleased me, but small suggestions of abstraction mixed with fantasy did creep into my

work, especially in some line drawings: “Herb People” & “Drug

People” and others (almost doodles, perhaps). York

with many paintings, as the first step towards London, where I would go to see my mother.

Although I had been away from New York and other painters for most of two years, my work

since 1943 had taken a jump towards fantasy. Animals were represented rather more often

than people, e.g. “The Sulky Lion”: hardly more than two-dimensional, the

buildings small and quite out of scale. “Tiger in the Sky”: similar, but more

three-dimensional; and from then on, distances increased, by ’43 giving the sense of

a place where you and the viewer might be. This is one of the characteristics I like about

Surrealism. It was also in the early ’40s that certain American Abstract painters

were gathering in New York. William Baziotes was the only one whose early work really

pleased me, but small suggestions of abstraction mixed with fantasy did creep into my

work, especially in some line drawings: “Herb People” & “Drug

People” and others (almost doodles, perhaps). |

| 1945 Bonestell Gallery18 E. 57th St |

In New York; the war continuing. In February, a solo

exhibition at the Bonestell Gallery, 18 E. 57th St. I was pleased

with the invitation with “Tiger in the Sky” and my name in bold print on the

cover – 16 paintings, plus ink drawings. I liked the way the

show looked, but nothing sold. I was still not participating enough in the New York art

world, I suppose. By now the Western countries had been freed from the Nazis; the Russian

Army was converging on Berlin from the east, the Western Allies from the west. In March,

Hitler and the other leaders surrendered, died or suicided in the ruins of Berlin. In

Asia, Japan was losing ground everywhere but refused to surrender. In August, the atomic

bombs were dropped. By early September I was on a liner for England, not a luxury one; it

was the New Amsterdam converted to a troop ship, meaning ten to twenty bunks to a

stateroom; and, for no understandable reason, since everything was still available in

America, no alcohol was served to the passengers, only to the ship’s officers!

Returning to what had been home, England, was a difficult experience, sad but heartwarming

at the same time. The country had been victorious but was on its knees, bankrupt from the

effort of holding out alone for nearly two years. Just about every necessity was to be

rationed for years to come. A remarkable amount of London was still there, but there were

gaps, big gaps. People were still good-tempered and cheerful, but the stimulus of holding

out against no-matter-what had gone, and left another kind of gap. However, absolutely

nobody every derided me for leaving; they were gracious and welcoming, and I soon made new

friends; several were from introductions in the U. S. some of which were important to me

for years to come. One of these was a Viennese art dealer, a refugee who also ran a

gallery in Mayfair right through the Blitz. He offered me an exhibition almost right away,

so the best thing I could do was to get myself a place where I could work and do more

paintings. I must say that I was longing to be back in America, but this was impossible;

one could not even pay the fare in pounds, so I painted the floor of my new flat bright

pink and acquired two cats. |

| 1946 Arcade GalleryOld

Bond St |

The show was set for January at Paul

Wengraf’s Arcade Gallery, Old Bond Street. It was the largest show I had yet had:

nineteen oils, twelve water-colors, eight pen drawings, two charcoal-pencil drawings from

student days with Ozenfant (1936-41). Quite well received; a collector immediately bought

“Woman with Cats” (1936-37), one of my earliest paintings. Later, this same

collector, a Mr. Rose, bought two of my best charcoal-pencil drawings, but, unfortunately,

I don’t know what happened to them after he died. ”Women with Cats” was

acquired by Lalita Frye. This and another of my paintings, “Rigidity and Mirth”

(late ’40s), she gave to an obscure young friend of hers sometime before she died. I

managed to trace them to his small house in Fulham, London, on a visit in ’96, rather

hidden from the world but loved. I also found that “Woman with Cats” was in a

group exhibition on cats at the Louise Hallett Gallery in Bayswater, London (I have the

address, but the gallery is not still there). |

Louise Hallett

Gallery, 1987 |

The show was in 1987, which of course is a long time after I

stopped painting; but it happens to be the year I started again. I certainly wish I had

happened to hear of it then; I could have made myself much less mysterious than I sound in

what is written in the catalog: “Stella Snead is a British Surrealist painter of

extraordinary quality about whom very little is known. She has been apparently very

private and unprolific, and the few works of hers that have come to light in the past

years are amongst the most interesting of the strong surrealist movement in this country

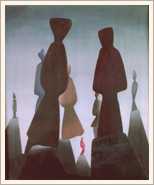

in the 1930s and 1940s.”  These months soon after the

war were often dreary; grey weather, time-consuming queues to buy the most meagre rations

almost prevented painting (solved by paying cleaning lady to stand in line and shop). The

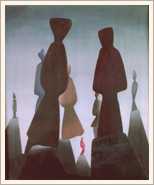

one painting I know I did at this time was “Advancing Monuments”; it was

something of a breakthrough – the figures were two-dimensional

shapes, but placed in the spaciousness of distance: a way of working which continued

through the rest of the ’40s, with, sometimes, the figures becoming

three-dimensional, also. That unexpected gift of seeing the paintings whole had more or less ceased, but ideas were still flowing from other angles and

interests: for instance, physical exploration of the planet. In those days I often heard

myself saying, “If I weren’t a painter I’d like to go on an

expedition.” I was fascinated by These months soon after the

war were often dreary; grey weather, time-consuming queues to buy the most meagre rations

almost prevented painting (solved by paying cleaning lady to stand in line and shop). The

one painting I know I did at this time was “Advancing Monuments”; it was

something of a breakthrough – the figures were two-dimensional

shapes, but placed in the spaciousness of distance: a way of working which continued

through the rest of the ’40s, with, sometimes, the figures becoming

three-dimensional, also. That unexpected gift of seeing the paintings whole had more or less ceased, but ideas were still flowing from other angles and

interests: for instance, physical exploration of the planet. In those days I often heard

myself saying, “If I weren’t a painter I’d like to go on an

expedition.” I was fascinated by the

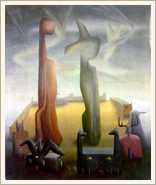

earth’s phenomena, the more spectacular the better –

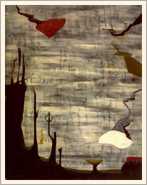

volcanoes, lava lakes, mudpots, geysers, waterspouts, tornadoes, twisters. A painting

called “Tornado” done at this time has a determined-looking twister at its

center as well as some quite abstract shapes, one of which is reminiscent of pre-Colombian

Mexico. the

earth’s phenomena, the more spectacular the better –

volcanoes, lava lakes, mudpots, geysers, waterspouts, tornadoes, twisters. A painting

called “Tornado” done at this time has a determined-looking twister at its

center as well as some quite abstract shapes, one of which is reminiscent of pre-Colombian

Mexico.

There was another painting, small, almost square, “The Green Witch.” I know

when I sold it (late ’40s, Taos), but not when I did it. It had an arresting shape in

the sky, and below this so-called witch are buildings as if made of adobe, some with

animal heads. This I might claim as a prophetic touch, as I had no thought of going

anywhere other than New York or California when I would finally get back to the States.

But shortly before I left London, in late summer, Taos, New Mexico, was to be my

destination. In this area of northern New Mexico, adobe has been the usual building

material since the Pueblo Indians started their village settlements here, long before the

coming of the Spanish Conquistadores, who in turn built their Mission churches of the same

mixture of mud and straw. In both Taos and Santa Fe today, there are many splendid houses,

even hotels, in the same building-style, though it is often reinforced by more easily

maintained materials.

Paul Wengraf had offered me a second show in September ’46, but I did not stay to

see it. It was mainly of the large charcoal-pencil drawings I had done as a student of

Ozenfant. So Taos was where I found myself in the Fall of ’46, in superb weather and

amid the most magnificent scenery up the Rio Grande gorge, some 80 miles north of Santa

Fe. The road, the only paved one in those days, brings you to what is surprisingly known

as Taos Valley, an extensive plain open to the west but contained on its other three sides

by higher mountains going up to 13,000 ft. Both Santa Fe and Taos are around 7,000 ft., on

this tail of the Rockies which dwindles to semi-desert flatness soon after Albuquerque, to

the south. I was enchanted, and particularly, by the arrangement of the land in the Taos

area; it was quite simply so satisfyingly right, it brought both serenity and excitement.

Furthermore, it was the first small, dominated-by-its-scenery place I had ever lived. My

house had just two adobe rooms, one with a corner fireplace made by an Indian woman; not

only was it good-looking, with its built-in adobe seat to one side, but it was of the kind

that never smoked. The wood we burned was piñon or cedar, and there was room for it to be

stored in my outhouse, assuring it of being continually sweet-smelling. For water there

was a tap in the yard (baths were taken when invited for dinner with friends). I loved it

all – that is, except for the gossip, everyone liking to know

what everyone else was doing.

I soon started doing some work and, during these nearly four years, did many of my

better paintings. Christmas, my first in Taos, was like no other, as our celebrations

included gong out to Taos Pueblo on Xmas Eve, where the two processions, one Indian, one

Christian, would meet and follow one another, bonfires blazing all around. The next day,

in snow or sun, the Indians would perform one of their mass dances in the wide space

opposite their five-storey village. |

| 1947 |

My tiny adobe house was between five and

ten minutes’ walk from the Taos Plaza, according to the weather – the

winters could be severe, the temperature dropping sometimes to 20 below zero, when walking

in either snow or slippery mud could be difficult. It was worth it; the surroundings were

so beautiful and the summers, ideal. I was content without a car, the long days of work

uninterrupted except when a friend would drive me to some viewpoint, or to a hidden

village where most people only spoke Spanish. I was fascinated again to feel how close to

the past these places were. If I had my own car it would have been impossible not to

wander too far too often, to go on and on into the inviting magic of this part of the

country. I had already found some very special places with the help of the mail-trucks in

1942, and was, in the not-so-distant future, to do much more exploring under quite

different circumstances, and in countries of whose existence I was then only vaguely

conscious. according to the weather – the

winters could be severe, the temperature dropping sometimes to 20 below zero, when walking

in either snow or slippery mud could be difficult. It was worth it; the surroundings were

so beautiful and the summers, ideal. I was content without a car, the long days of work

uninterrupted except when a friend would drive me to some viewpoint, or to a hidden

village where most people only spoke Spanish. I was fascinated again to feel how close to

the past these places were. If I had my own car it would have been impossible not to

wander too far too often, to go on and on into the inviting magic of this part of the

country. I had already found some very special places with the help of the mail-trucks in

1942, and was, in the not-so-distant future, to do much more exploring under quite

different circumstances, and in countries of whose existence I was then only vaguely

conscious.For the present, in this Spring of ’47 I was most content to be

stationary in this tiny town, feeling little or no nostalgia for the big cities. Except

for those moments of doubt and hesitation, painting was an absorbing and satisfying

occupation. I thrived on it, was never bored. And there was variety here –

the weather; new phenomena, such as complete double rainbows; clouds imitating the

flat-topped mesas; shooting stars, sometimes showers of them; a moonbow; black skies

heralding storms; but more sun than anywhere else I had lived, together with refreshingly

cool mornings and evenings, due to the altitude. And new people: our population of 2,000

rose in summer to 3,000. There was a small upheaval ahead of me, as I had promised my

mother I would return to London for a couple of months in the summer. I streaked

cheerfully through New York, languished a little in London, was soon back to the sun and

sagebrush. Exhibits were getting set up; I believe I did most of them myself but cannot

clearly remember how or when. Of course, showing in Taos or Santa Fe was easy; Taos had

almost as many galleries as there were artists. |

Santa Barbara;

San Diego; U.

Of N. Mexico;

Los Angeles |

As well, during the next two years, I had solo exhibitions in

the Santa Barbara and San Diego Museums, at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, and

at a gallery in Los Angeles. |

| 1948 |

Another year, for me, happily similar to the last, weathering

the winter, forever putting on and taking off boots, welcoming the return of my two male

cats from their nights out (they longed to melt the icicles hanging from their tummies on

my bed but had to be diverted to the rug by the fire). We artists dined at each

others’ houses; I accommodated up to six, even without a table, cooking on kerosene,

with a small Dutch oven. The tap in the yard would sometimes freeze, but how rewarding it

was to wrap its foot-high stem in newspaper soaked in kerosene, light it and see the water

flow again. This wee house cost me all of $15 a month. The summer slowly and gracefully

enveloped us; and this year, I stayed in Taos. On the edge of town there was a swimming

pool with no facilities, except that it was warmed by a hot spring; we could swim by night

(as well as by day) lit by the headlights of a car or the moon. In the town there were

several places to dance; in those days, we still danced with partners. One dance was the vasaviana,

left behind by the Spanish – a rose in the teeth, why not?

I don’t think the other resident artists were much interested in my painting; most

were moving headlong into abstraction, so, again, I was not part of a group. This seemed

to be a repeating pattern for me; I wondered, was it good or bad? Perhaps I had more

talent for remaining an outsider than for anything else. Should I worry? I hardly could,

with the urge to go my own way pushing so firmly and spontaneously; but I noticed that I

made a few sales, and also, that peoples’ comments on my work, mainly from visitors

or strangers, were often wildly contradictory, ranging from “highly spiritual”

to “brazenly pagan”: a little disconcerting and puzzling, as I was not inclined

to interpret my paintings in either of these ways, thinking of myself as very much a

visual person. I was and am still enormously pleased and stimulated, or repelled, by the

look of things, be they real and tangible, in the outside world, or arrangements of form

and color. My paintings are not telling a story, nor are they making a statement; yet,

they are not truly abstract. They are showing a place, nearly always three-dimensionally

real, yet a fantasy.

One of the Taos galleries, run by a woman and friend of mine, had arranged to take a

large group of Taos artists to Palm Springs, a well-known resort and a center for

earthquakes. I and several of my pictures were greeted by just that: an earthquake, a

smallish one but with repeated after-shocks. We were invited for cocktails by an elderly

British expatriate couple, the kind who would know how to behave in whatever circumstance.

The whole house shook. The wife, glancing at the ceiling, remarked to the husband, “I

think that’s a new crack dear, don’t you?” All we did was sip and make

agreeable conversation. The shocks continued into the night, but my friend and I had

acclimatized quickly; we slept and awakened next morning to a still and steady day. That

evening, at the opening of the exhibition, the martini glasses could be filled to the

brim. There were film stars; it seemed a success, but I don’t know how many sales:

none for me; I didn’t mind. Selling did not interest me very much; I fact, I liked having

my paintings, and the important thing was always to do a satisfactory job on each one. |

| 1949 The

London Gallery, 23 Brook St |

Another visit to England during the summer, and a firm

arrangement withThe London Gallery, 23 Brook Street, for a solo show there in May 1950. It

was the leading gallery in London, at that time, devoted to Surrealism, directed by E.L.

T. Mesens, poet, long closely connected with André Breton and the Paris Surréalistes. In

this exhibition much of my work done in New Mexico would be shown internationally for the

first time. In the next room was to be a Homage exhibit to the well-known collageist Kurt

Schwitters, who died in ’47. |

| Carnegie

Int’l Exbt, Pittsburgh |

This year, 1949, my painting “Advancing Monuments,”

was chosen to be shown in the Carnegie International Exhibition in Pittsburgh,

Pennsylvania. These were encouraging signs. Back in Taos that Autumn, life took on a

fresh bloom with a new relationship, one that seemed to promise permanence; and, after the

show in London, an extended sojourn in Europe. |

| 1950 |

There was much packing to leave

Taos, and much to be left behind. We left in the early months of 1950, for New York, and planned to

be in London by March. Then came the signs of break-up. I couldn’t understand it, nor

could I stand it. This lover was leaving me; and for the first time I realized that I had

always done the leaving. I had never been left before. I cracked up. I was in smithereens,

could hardly speak. I remembered my mother telling me that, after they put my father in a

home for the deranged, he did not speak for a year; just as my father had not been able to

organize himself to be a barrister, which he had worked for and planned to be, I could not

even face my exhibition. Some friends wrote, offering sanctuary. They lived on the slopes

of Mt. Palomar in California. early months of 1950, for New York, and planned to

be in London by March. Then came the signs of break-up. I couldn’t understand it, nor

could I stand it. This lover was leaving me; and for the first time I realized that I had

always done the leaving. I had never been left before. I cracked up. I was in smithereens,

could hardly speak. I remembered my mother telling me that, after they put my father in a

home for the deranged, he did not speak for a year; just as my father had not been able to

organize himself to be a barrister, which he had worked for and planned to be, I could not

even face my exhibition. Some friends wrote, offering sanctuary. They lived on the slopes

of Mt. Palomar in California.My work was well on its way to London, while I went west,

in the opposite direction. A friend from Taos was in New York, and she accompanied me as

far as El Paso, I being, I am ashamed to say, the most dreary of travelling companions.

Mt. Palomar was a special place; again I was near the world’s largest telescope, this

time the 200-in., now on its summit. My friends were painters, owned a vast amount of land

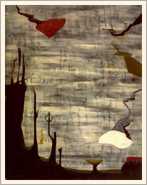

and had four cats who took walks with us in this wild area. I began to be soothed, and

tried to get back to painting – smallish, modest, stilted, sad

they were, their centers often blank, with awkward, angular, spiky shapes around the

edges. Where had the exuberance gone?

Fortunately, perhaps, it was decided we would drive to New Orleans and see something of

the Caribbean by taking small boats. We were out of date, there were no such boats. We

took a banana boat to Cuba, then managed to get to Jamaica, which then was like smooth

velvet after the noisy brashness of Cuba. It was out-of-season August, and rather

pleasant. I think we may have flown back to Miami, where we parted, my friends going to

pick up their car in New Orleans, I taking a bus to New York. I had nothing else to do but

go to London and find out about my show. The news was not good; more precisely, there was

no news: perhaps this was my least-noticed show. But here and now, emptiness surrounding

me, I found the most attractive flat, so why not try living in London again and pay more

attention to my mother – she was overjoyed. I even acquired a

pregnant poodle. The flat had a 14-year lease, which I signed. The mistakes were piling

up. My longest depression established itself, with only the briefest up-spells; it lasted

two-and-a-half years. Being in England was difficult; perhaps I could do better in

America. I got back probably at the end of 1950; my ever-loving and patient mother coped

successfully with the 14-year lease. |

| 1951 |

Being in trouble in America means going to a psychiatrist. A

Dutch Jungian was found and highly recommended. He had an interest in the arts, was a

collector – a Feininger hung over the fireplace; he was kind,

supportive and interesting, even though I wept much of the time at the beginning. Later, I

started selling textiles as a free-lance agent; they were mostly those of other people.

Occasionally I made a sale, and once it was of one of my own designs. I felt less than

half a person. After nearly a year, and countless sessions with the doctor, I started

thinking how vacuums are likely to be filled, so let’s stop trying, relax, and see

what was going to fill my vacuum. I stopped the psychiatry –

perhaps it was early 1952. |

| 1952 |

And along came an invitation to go to India, a place to which

I had never thought of going. A new idea. I was stirred. It came from a young woman, Didi,

I had met while living in Taos, who had gone to college, met and married one of the

[Asian] Indian students. In 1951, with one child already, they returned to India, to live

joint-family in a small town, Nasik, 115 miles northeast of Bombay. My mood was already

rising during the summer of ’52. It was not a zooming-up, but rather a quiet creeping

from under the long, stifling depression. We, Didi’s mother and I, left England for

India by ship in November ’52. Before I had even set foot in India, while the ship

was waiting “in the stream,” as they say, for a place to dock, and we could see

the Gateway of India and the Taj Mahal hotel, I became enormously excited to be there. On

landing we were driving almost at once up to Nasik, the country somehow resembling New

Mexico, only greener and more cultivated, the heights flat-topped like the mesas. For two

weeks I hardly slept, just kept on saying to myself, with amazement, “I’m in

India!” I was not even thinking of my vacuum, that space left by not being a painter.

It was some weeks before I realized it was being filled by India itself, its sights, its

people, its ways of being, its un-selfconscious beauty, even its ugliness. It no longer

mattered that I was not a painter; there were other ways of filling a life. |

| 1953 |

At this point, I had no clear idea of what exactly I was

going to do. I was simply absorbing with gusto. The plan had been to stay six months. In

mid-year, I decided I couldn’t leave. I had been doing much lone traveling on the

grand old British trains then still in general use, nights in the bungalows built for the

British civil servants, or in station waiting-rooms. After one such night, with the

addition of bedbugs, I wrote to my mother that I could not bear to leave. I stayed on for

all of 15 months. From time to time I came back for rest and the feeling of belonging to

the most-hospitable Nasik family; sometimes I wrote small pieces on this or that

happening. I was learning the ropes of India. And I was very, very happy. |

| 1954 |

In February, I returned via England to the States. Lived in

sublets in New York, slowing planning a return to India, this time overland, on the

surmise that if there were roads there must, or at least might be, busses. It seemed to me

a most intriguing project. It was important not to hurry, to move unpredictably, certainly

in a leisurely fashion, making detours; no deadlines. I’ve always liked the idea of

travelling without reservations. No companion was found who had this amount of time – say, three or four months – and,

furthermore, I felt quite capable of doing it alone. I hardly spoke of it to my mother, at

first, but got down to reading books by earlier travellers to the Middle East, Persia,

Afghanistan. |

| 1955 |

My mother had turned eighty, and she had never been to New

York. I suggested a visit and got a big, enthusiastic yes. We had been getting on much

better since my India sojourn. She came in June. All prejudices dropped away: she loved

teabags, the skyscrapers, finned cars in pastel colors. Among my friends, her favorite was

a black film maker, with car, who drove her over the bridges and through the tunnels; a

Chinese who made animated films; a Russian woman mad about black traditional dancers. The

New England-types she liked less. All together, it was a happy visit. We returned to

England first-class on a French liner (she would never fly), I being vegetarian all the

way, as I had never dared tell her I now ate everything. |

| 1956 |

January— mother less well. She was brought to my flat,

as she refused to go to a hospital, as she distrusted conventional medicine. After two

weeks she died of a blood clot. It seemed an easy death. By April, I was free to leave. I

flew to Istanbul, and from there, one of the most wonderful journeys I ever made started,

via Turkey, Syria, Jordan, Iraq, Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan and India, and into the arms

of the Nasik joint family. I was suitably tired, and perhaps more acceptable? Anyway, glad

to stay still and start writing the book [probably GO WITH GOOD LUCK]

on the trip. I did not realize at the time that I had had two releases –

my mother’s death, and the release from painting into travel. By seeing black and

white darkroom work for the first time, a new passion had seized me: to be a photographer

and do my own printing. |

next: Chronlogy, Part 2

|

![]()