e s s a y

Pavel Zoubok Stella Snead has traveled to many places in her life and work. Her decision to become a painter during the mid-1930s, in her native England, marked the beginning of a long love affair with places unknown, both real and imagined. During her studies in London with the French painter Amedée Ozenfant, she developed a meticulous draftsmanship and sure taste for the fantastic imagery of Surrealism, which in 1936 made its first major appearance in England. There she worked alongside fellow artists Leonora Carrington and Sari Dienes. When the possibility of war threatened Europe, however, Stella Snead felt it imperative for herself and all “makers of culture” (painters, poets, intellectuals, etc.) to flee Europe for America, as many did. In November 1939, she boarded a ship bound for New York.

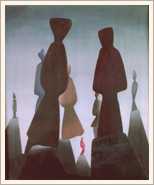

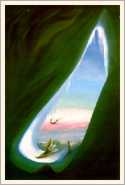

Stella Snead’s long hiatus from oil painting after 1950, and subsequent career in photography, should not be interpreted as an abandonment of her distinctly Surrealist sensibility. Rather, many of the formal and thematic concerns of her paintings are echoed in her photography. A long and fruitful association with India, a country whose visual culture is vivid with fantastic imagery, demonstrates her continued interest in the disjunctive language of Surrealism. In India she photographed the oddities of street life, the mysterious and abstract worlds formed by natural patterns in the sand, and the strange and wonderful iconography of Hindu sculpture. Her photographic work resulted in the publication of eight books, including SHIVA’S PIGEONS (1972), BEACH PATTERNS (1975), and ANIMALS IN FOUR WORLDS (1989). During the 1960s and 1970s, Snead’s photography became more explicitly Surrealist, with a series of black and white photo-collages. These strange, playful works, constructed from documentary photographs of her travels, set the stage for her return to painting during the late 1980s. By cutting and pasting, Stella Snead constructed a dream-like vision of reality from the literal fragments of her own experience. Her paintings had represented an expressly formal consideration and abstraction of places and things seen, or experienced. By contrast, her photo-collages were more emphatically poetic, or literary, in their displacement and reconstruction of memory. When one considers the histories of women artists who were associated in varying degrees with the Surrealist movement, it is easy to understand how Stella Snead’s career as a painter could go almost completely undocumented. Unlike certain of her female contemporaries, she was never publicly associated with the Surrealist group. During the short but fruitful period in which she was painting, however, she enjoyed no less than eleven solo exhibitions, three of them in museums. While many of the more widely-known women Surrealists had professional and/or romantic associations with their male colleagues, Stella Snead had none. Despite her personal and professional autonomy from the official ranks of the Surrealists, certain aspects of her painting place her firmly within their theoretical and aesthetic traditions. Like many of her female contemporaries, she turned to nature and to her own experiences for inspiration. By contrast, however, she did not employ self-representation and narrative structure as vehicles of communication, but, rather, conveyed her thoughts and feelings through a distinctly Surrealist vision of the physical world. Collaboration was an important characteristic of the Surrealist enterprise. Personal and professional associations between the groups members came to fruition in numerous joint publications by Surrealist poets and painters, in the iconography of their paintings and collages, and, perhaps most effectively, in the visual products of the Surrealist game of Cadavre Exquis. Stella Snead’s art, however, reflects a distinctly solitary nature. Her decision to become a painter represented an escape from the stifling boredom of conventional English life and was a decisive move towards selfhood. Surrealism provided her with an aesthetic and ideological framework within which to express herself. To pursue an active participation in the Surrealist group would surely have meant giving up a good deal of her autonomy. It is important to note, however, that despite Snead’s marginal participation in the activities of the official Surrealist group, she has always considered herself a Surrealist. What is apparent when looking at Stella Snead’s recent variations

— paintings loosely based on earlier works that were either destroyed or stolen

— is the consistency of her artistic vision. Her return to painting after 1987

coincided with the rediscovery of certain lesser-known Surrealists by curators, critics,

and collectors. Significantly, the rise of Feminism during the 1970s, and its lasting

impact on the art world, brought international recognition to women Surrealists such as

Leonora Carrington, Leonor Fini, Frida Kahlo, and Dorthea Tanning. Stella Snead reentered

the practice of painting with a knowledge that the histories of these women and others

were finally receiving

___________________ next page |